A friend whose child is in college and thinking about going for a Ph.D. called me recently. “You work in admissions, Gerry; will you talk to my daughter about how to ensure that she’s ready to put forward a strong application?” You shouldn’t have to know someone who works in the field to get this sort of advice! So, in an attempt to make this available for everyone, here are a few of the key insights that I have.

Time: You Can Never Have Enough of It

One thing I highlight to everyone considering graduate school is the importance of giving yourself plenty of time to research programs and complete the application. If you decide in November to apply for Ph.D. programs that will largely have December or January deadlines (The programs at the CUNY Graduate Center, where I work, have deadlines in December and January.), you are setting yourself up for difficulties. You need time to research programs, get application materials together, tweak your applicant statement for each school you apply to, talk to folks who might write letters of recommendation for you, and maybe time to study for the GRE (and TOEFL/IELTS, depending on where your previous degree(s) are from).

This means that the more time you have, the better. If Ph.D. deadlines are looming and you are just starting the process of researching programs, it might be worthwhile to wait a year and apply to the next cycle. That way you will have ample time to work on all of the pieces of the application and can put your best foot forward. If you do decide to rush to get your applications in quickly, be kind to yourself if you aren’t admitted and reapply for the next year under better circumstances.

Finding the Right Program to Apply to Is Key

Having plenty of time before a deadline allows you to do your most important piece of prep work for the Ph.D. application: researching programs. A program wants to ensure that the students they admit will have the coursework and faculty mentoring that they need to thrive (and finish!), so they want applicants to be a good intellectual match. As a student, this is what you want from the program too! So if, for example, you want to study Southeast Asian history, but you look at a school’s faculty profiles and coursework and see that the Ph.D. program in history is mostly focused on the West, you know that you might not be a great fit for each other. If you aren’t a good fit, it’s less likely that you’ll be admitted. Ideally, your first step toward finding potential programs would be to ask faculty whom you trust to help you with narrowing down a list of schools; because they are scholars in the field, and because (one hopes) they know what sort of work you are hoping to do in your Ph.D. program, faculty mentors will often have a few suggestions to get started. Next, consider the articles or books that have influenced your thinking in the area that you want to pursue. Look at the programs where these faculty work because you now know that this school will have at least one faculty member who will have overlapping research interests with you. Once you browse the bios and CVs of other faculty in the same program, you can see if there are others there whose work excites you as well. If there are, it’s probably a good school to keep on your list! Finding the right Ph.D. programs to apply to is a difficult and time-consuming, but vital, step in the process. It can be a little demoralizing too, if you feel that you cannot move to a new place (for family or other reasons) for the degree because you might find from your search that the schools closest to you do not actually have programs that are the best academic fit. Very few Ph.D. programs (and even fewer reputable ones) are offered online, so whenever possible be prepared to move to a new city or state.

Letters of Recommendation

Every program that you apply to will require at least two (sometimes more) letters of recommendation. Ph.D. programs will almost always prefer academic letters (in other words, letters from someone who has had you in class and/or worked with you on research or another academic task) over professional letters (like those from a supervisor). Letters from friends or family are not appropriate.

When you ask someone for a letter of recommendation, if that person does not give you a very enthusiastic “yes” when you ask them to write it, I would encourage you to move on and ask someone else. People who are excited to recommend you will be more likely to write thoughtful letters tailored to your personal strengths and interests. You don’t want someone who writes two sentences that basically say, “This person got an A in my class and I’m sure they will do fine in your Ph.D. program,” since that doesn’t speak much to why you are a distinctive student. To help gauge their response to your request, my advice is to ask them in person (or at least via Zoom), as it is very hard to gauge body language and tone of voice if you only ask via email.

Be prepared to provide some basic documents for your letter writers, should they request them. Many will want to see a draft or outline of your applicant statement. Sometimes they will ask for a copy of your transcript as well. At the very least, have a list of all of the schools that you plan to apply to ready, so that they know how many versions of the letter they will need. With that list, let them know how each of the schools would like the letter to be sent—some will want a mailed hard copy, some will take them by email attachment, and some will have those writing them upload the letter directly.

Money Matters

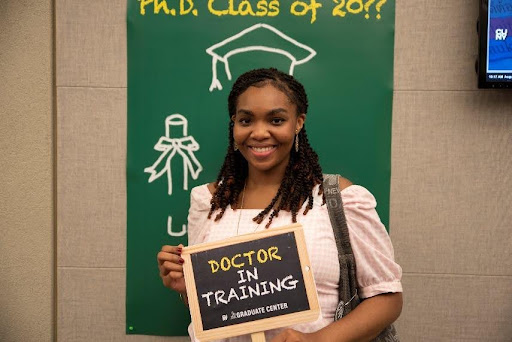

In the vast majority of cases I would not recommend applying to schools where there is limited Ph.D. funding available. A Ph.D. is going to take you at least five years to complete—and that’s if you are lucky, as nationwide the average time to degree is actually over eight years. Many programs will require that you maintain a full-time course load during the Ph.D., and to have a schedule flexible enough to take classes whenever they are offered. Ideally, you want to get into a program that will offer you a funding package that includes free tuition and a stipend to support you. Some funding packages will come with low-cost health insurance as well—especially at schools where Ph.D. students are unionized. For reference, the CUNY Graduate Center does offer health insurance, and grad students are unionized. You should note that, depending on the generosity of the school (plus whether it’s in an area with a high cost of living), you might need to take on a part-time job to supplement the stipend. If you are not offered a stipend, at the very least you should receive a fellowship or scholarship that offers free tuition. My school offers many such fellowships, including some specifically for students from underrepresented groups. If there is neither tuition nor a stipend on offer, I would encourage you to rethink your desire to join that Ph.D. program; if you are paying to be there, you are likely going to be subsidizing everyone else in the room, and you may be taking out loans to do so!

Closing Thoughts

As you put together your application, my final piece of advice is to really pay attention to details. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen an applicant statement that gives the wrong school name, or that hasn’t been edited to discuss why the person is a good academic fit for a particular program. The statement should be adjusted a bit for each school you apply to—don’t just write one statement and use it interchangeably! If a program asks for a 15-page writing sample, they may be forgiving if you give them a 17-page one, but if you submit your entire undergraduate thesis, they are more likely to be irritated. If you are specifically asked to provide something in CV format rather than résumé format, note that and make the edits. However many times you read articles like this one, you will inevitably have questions along the way; ask for help if you can’t find the answers. For academic questions, you will probably want to reach out to Ph.D. programs directly; for questions about the application process, reach out to the school’s admissions office. You don’t have to be related to a friend of an admissions officer to get the help that you need.

Gerry Martini is an associate director of admissions at the CUNY Graduate Center (a member of the Alliance of Hispanic Serving Research Universities) and co-chair of the CUNY-wide Graduate Admissions Council. He counsels students interested in applying to doctoral and master’s programs at the Graduate Center and leads admissions workshops and information sessions. He holds an M.A. in political science from the Graduate Center and a B.A. in political science and government from Albion College.

Thank you for your excellent and informative piece, Gerry. I’m planning to apply to a graduate program for next year, and this article came at just the right time for me. My interests are the M.S. in Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences at CUNY Graduate Center, as well as the M.S. in Data Science at CUNY SPS, among others… Do you have any advice for those of us looking for fully funded master’s programs?